2024 Year in Review

On this page

- Message from the Chief Justice of Canada

- Judges of the Supreme Court of Canada

- Message from the Registrar

- Canada’s final court of appeal

- An essential part of our democracy

- Judgments of the Court

- Outreach and education

- International engagement

- 150 years of the Supreme Court of Canada

- Connect with the Court

- Statistics

Hello! I’m the Chief Justice of Canada and I’m pleased to invite you to read our Supreme Court 2024 Year in Review.

This report offers a snapshot of our work – both inside and outside the courtroom. As judges, we have a responsibility to share our work and explain what we do. This report is one of the many ways we build and maintain trust in the Canadian justice system.

An independent and effective judiciary is more important than ever. I understand that people may be concerned about what they are seeing around the world. I am too. But rest assured that respect for the rule of law in Canada is strong. We have protections for judicial independence and a culture of openness in our courts. We are constantly working towards improving access to justice. These values help ensure fairness, transparency and the impartial application of the law.

In the 2024 Year in Review, you will find examples of this and more.

Thank you for trusting us with the important task of upholding the rights and freedoms of Canadians.

Message from the Chief Justice of Canada

Since my appointment to the bench more than 20 years ago, I have made it a priority to promote open courts, access to justice and judicial independence. These 3 principles work together to uphold the fairness and integrity of our judicial system. Each one supports the others, ensuring that justice is transparent, accessible, and impartial.

In our democracy, legitimacy depends on public trust in the judicial system, and confidence is built and maintained when these principles are upheld. That is why I am committed to ensuring a judicial system that is open and transparent, accessible to the public and free from outside influence.

In 2025, the Supreme Court of Canada is commemorating its 150th anniversary. This important milestone gives us an opportunity to reflect on our past and future. It is also a chance to remind Canadians of the Court’s role in our justice system and our democracy. We have many engaging anniversary initiatives planned throughout the year aimed at members of the judicial, legal and academic communities, the media, and most importantly, the general public. These activities will promote greater awareness of the Court’s role and function, while further strengthening public confidence in the Court and our justice system.

In an era where misinformation and disinformation are so pervasive, judges and courts must do everything they can to explain who they are and what they do. Trust in our institutions depends on it.

To that end, it is my pleasure to present the Supreme Court of Canada’s 7th annual Year in Review. In my view, reporting back on our work is essential, because our decisions have a significant impact on the lives of citizens. I trust that you will find value reading about our work and decisions, and the various ways we are nurturing broader understanding of our Court’s role in the Canadian justice system.

For those who consult this report each year, you may notice a few changes. In this edition, we have put greater emphasis on our judicial work, and streamlined how we present statistical data, making it easier to interpret. These refinements will help promote openness and access to the Court. You can also find ample information on our work on our newly revamped website.

Over the next year, we will continue to build on these efforts and further engage with Canadians on our role and history.

I hope you enjoy our 2024 Year in Review, and I invite you to join us this year to mark our 150th anniversary!

Chief Justice of Canada

Judges of the Supreme Court of Canada

Chief Justice of Canada Appointed to the Supreme Court in 2012

Appointed Chief Justice in 2017

Message from the Registrar

As Registrar of the Supreme Court of Canada, I am privileged to lead the remarkable team responsible for the administration of Canada’s final court of appeal. I am very proud of our employees and their dedication to provide services and support to our 9 judges, allowing the Court to process, hear and decide a high volume of cases each year. They are crucial to support communications and outreach to various stakeholders to promote understanding of the Court’s role and enhance access to justice and judicial information.

The environment and context in which the Court manages and decides cases is continuously evolving, which presents us with new challenges, but also new opportunities. Building on the success of the electronic filing portal that we first introduced in 2023, the Court is leveraging new technologies to streamline case administration. Our new website, which launched at the beginning of this year, is just one such measure that improves the discoverability of information and enhances access to case files. Access to justice and court modernization go hand-in-hand and these initiatives support the Court’s commitment to key judicial principles of openness and transparency.

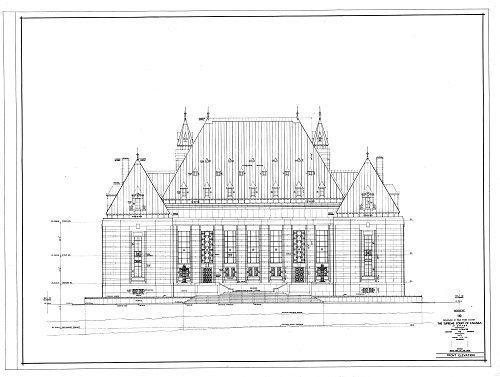

Meanwhile, planning is well underway for the rehabilitation of the Supreme Court of Canada building in the coming years, during which the Court will relocate to the West Memorial Building. I am confident that this preparation will ensure a smooth transition for judges, staff, counsel and members of the public.

We are eager to share in the commemoration of the Court’s 150th anniversary in 2025, by supporting the myriad communications and outreach activities planned throughout the anniversary year.

I am incredibly proud of our ongoing efforts to foster a safe, inclusive, and diverse workplace, while supporting the professional growth of every employee. As 2024 drew to a close, I was pleased to recognize all those who reached milestones over the previous year during our Long Service Award Ceremony. It also provided an opportunity to celebrate employees’ spirit of giving — staff raised an incredible $37,400 as part of the Court’s annual Government of Canada Workplace Charitable Campaign (GCWCC).

I am proud of our achievements during the past year and look forward to continuing to work collaboratively in providing excellent services for our judges and our institution in 2025.

Registrar, Supreme Court of Canada

Canada’s final court of appeal

Established in 1875, the Supreme Court is Canada’s final court of appeal. As the highest court in the country, it has final jurisdiction over disputes in every area of the law. Since its inception, the Court has played a crucial role in shaping Canada’s legal landscape, providing the foundation for a strong democratic country founded on the rule of law.

The Supreme Court of Canada consists of 9 judges, including the Chief Justice of Canada. All judges are appointed by the Governor in Council. By law, 3 judges must come from Quebec, to adequately represent the civil law system.

Bilingual and bijural

The 9 judges hear and decide cases in both English and French. The Court is also bijural, which means it applies the law according to our country’s common law and civil law legal traditions.

There are no trials or juries at the Supreme Court. Judges consider written and oral arguments from the main parties, and ask them questions. They may also hear from interveners, who serve an important role in bringing broader perspectives before the Court.

The Supreme Court is open, impartial and independent, and is respected around the world for its culture of judicial excellence. It is an active and valued member of several international organizations, and it regularly participates in judicial exchanges with other apex courts around the world.

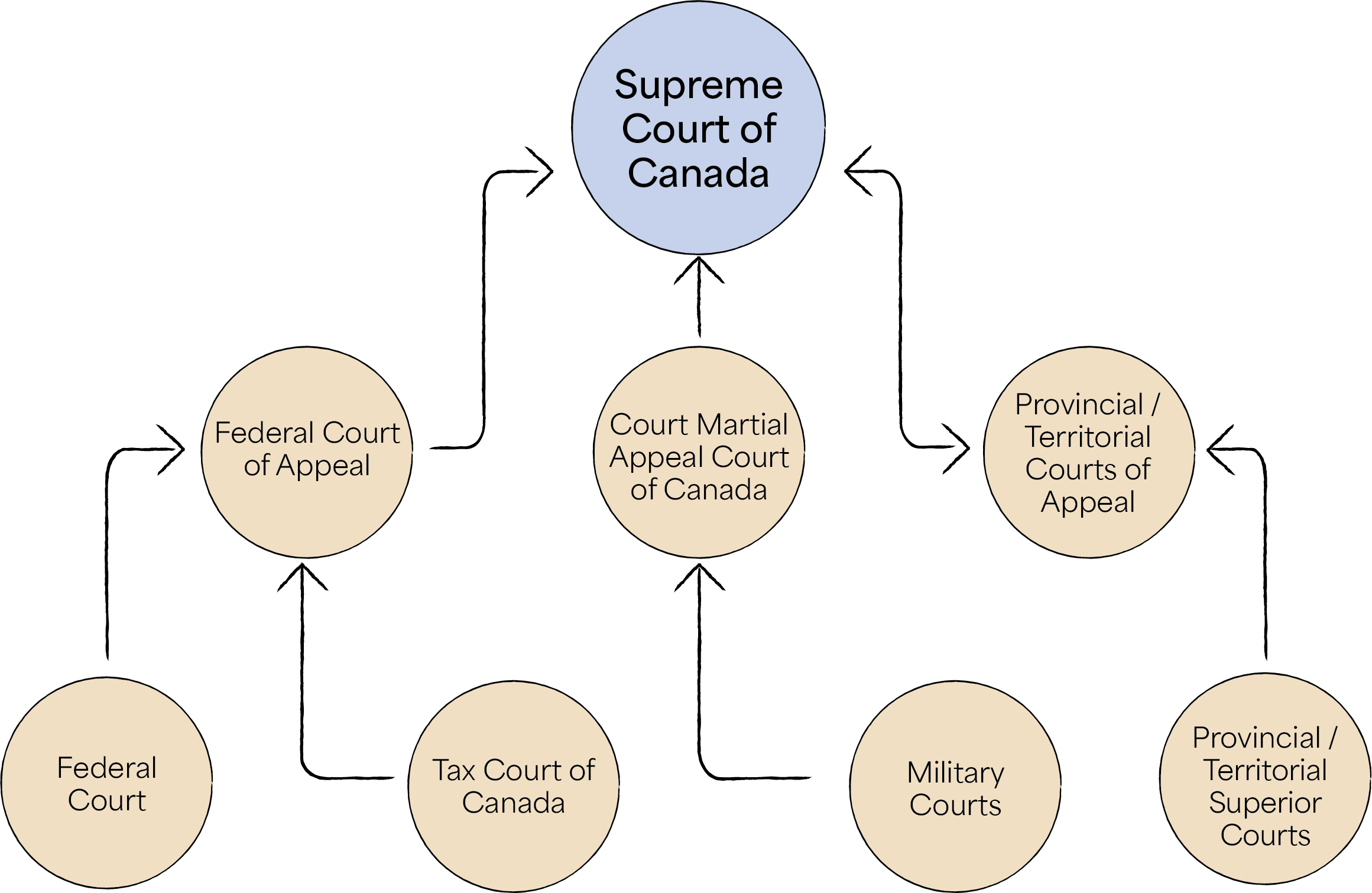

How the courts are organized in Canada

The federal, provincial and territorial governments have varying responsibilities for the judicial system in Canada.

The Supreme Court of Canada is the highest court in our judicial system — Canada’s apex court.

An essential part of our democracy

The 3 branches of government

Canada’s Constitution lays the foundation for our democracy by defining the 3 branches of government:

- the legislative, tasked with creating and passing laws;

- the executive, responsible for deciding policy and overseeing the government’s day-to-day operations; and

- the judicial, responsible for interpreting and applying the law and the Constitution.

Each one has separate powers and responsibilities that are defined in the Constitution: the legislative branch passes laws, the executive implements them, and the judicial interprets them.

Judicial independence

Separating the judiciary from the other 2 branches ensures a key principle of our system of government: judicial independence.

Judicial independence means that the judiciary has the ability to make decisions based solely on fact and law, free of any influence from government or outside parties.

Few principles are more important to the preservation of the Rule of Law, democratic values, and fostering public confidence in our institutions.

An accord between the Chief Justice of Canada and the federal Minister of Justice was signed in 2019 to strengthen the independence of the Supreme Court of Canada.

“Judicial independence isn’t for judges, it’s for the public. It ensures judges can uphold the rule of law, the Constitution and rights and freedoms without interference or intimidation.”

— The Right Honourable Richard Wagner, P.C.

Chief Justice of Canada

First adopted in 2021, the Supreme Court of Canada’s badge, emblem and flag visually express its role and traditions while symbolizing the fundamental principle of judicial independence.

Judgments of the Court

In 2024, the Supreme Court of Canada delivered judgments on a variety of cases originating from across Canada. The decisions affect many areas of the law, including the admissibility of evidence in criminal matters, language rights, bankruptcy and insolvency, and much more.

Several cases involved Indigenous rights, such as self-government, historical treaty rights and the reconciliation of constitutional protections under sections 15 and 25 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Another key theme was the open court principle, where the Court balanced the presumption of openness in judicial proceedings with the rights of participants. This included cases involving the protection of a sexual assault complainant and the confidentiality of an informant.

Every case before the Supreme Court is significant and contributes to the ongoing evolution of Canadian jurisprudence.

How cases come to the Supreme Court

Cases come to the Court in 1 of 3 ways:

-

Leave to appeal: In most cases, a party must ask the Court for leave (permission) to appeal a decision from a lower court such as the provincial and territorial appeal courts, the Federal Court of Appeal or the Court Martial Appeal Court of Canada. The Supreme Court will only hear cases that meet the test of public importance of an issue of law or mixed law and fact, as set out in section 40 of the Supreme Court Act. The Court does not give reasons for its decisions on leave applications.

-

As of right: In some instances, leave is not required as parties have an automatic right to appeal. For example, in some types of criminal cases, an appeal may be brought before the Court as of right when 1 judge in the court of appeal has dissented on a point of law. A party can exercise their right to appeal as of right by filing a notice of appeal.

-

References: The Court also hears references, which are requests from a government for an advisory legal opinion. Reference cases often ask if a proposed or existing legislation is constitutional. The Supreme Court has answered a wide variety of reference questions over the years, on topics such as climate change, same-sex marriage, Senate reform and more.

A landmark decision

2024 SCC 5 | February 9, 2024

On February 9, 2024, the Supreme Court issued a landmark decision upholding the constitutionality of a federal statute affirming Indigenous peoples’ right of self-government with respect to child and family services.

In 2019, Parliament passed the Act respecting First Nations, Inuit and Métis children, youth and families (Act), which establishes national standards and provides Indigenous peoples with effective control over their children’s welfare. In addition, the Act specifies how its provisions and Indigenous peoples’ jurisdiction to make laws in this area will interact with other laws. Section 21 gives the laws made by Indigenous groups, communities or peoples the same force as federal laws, whereas section 22(3) states for greater certainty that Indigenous laws prevail over provincial laws to the extent of any conflict or inconsistency.

After the Act was passed, the Attorney General of Quebec asked the Quebec Court of Appeal to determine whether the Act was ultra vires Parliament’s jurisdiction under the Constitution of Canada. In other words, the Attorney General asked whether, in light of the division of federal and provincial powers under sections 91 and 92 of the Constitution Act, 1867, Parliament had exceeded the limits of its jurisdiction by passing the Act. In the opinion it provided in answer to that question, the Court of Appeal concluded that the Act was constitutionally valid except for sections 21 and 22(3), the provisions giving the laws of Indigenous peoples priority over provincial laws.

The Attorney General of Quebec and the Attorney General of Canada both appealed to the Supreme Court of Canada from that opinion. The former argued, among other things, that the entire Act impermissibly intruded on certain areas of exclusive provincial jurisdiction. The latter countered that the Act was a valid exercise of Parliament’s legislative jurisdiction over “Indians, and Lands reserved for the Indians” under section 91(24) of the Constitution Act, 1867.

A unanimous Supreme Court dismissed the appeal of the Attorney General of Quebec and allowed the appeal of the Attorney General of Canada. The Act is not ultra vires Parliament’s jurisdiction under the Constitution of Canada. In a unanimous judgment, the Supreme Court ruled that the Act as a whole is constitutionally valid. The essential matter addressed by the Act involves protecting the well-being of Indigenous children, youth and families by promoting the delivery of culturally appropriate child and family services and, in so doing, advancing the process of reconciliation with Indigenous peoples. The Act falls squarely within Parliament’s legislative jurisdiction under section 91(24) of the Constitution Act, 1867.

The Court characterized section 21 of the Act as simply an incorporation by reference provision. Through section 21, Parliament has validly incorporated by reference the laws, as amended from time to time, of Indigenous groups, communities or peoples in relation to child and family services. As for section 22(3), the Court affirmed that it is simply a legislative restatement of the doctrine of federal paramountcy, under which the provisions of a federal law prevail over conflicting or inconsistent provisions of a provincial law.

“Under this framework created by the Act, Indigenous governing bodies and the Government of Canada will work together to remedy the harms of the past and create a solid foundation for a renewed nation‑to‑nation relationship in the area of child and family services[…].”

Other notable decisions

This appeal dealt with the question of whether an internet protocol (IP) address attracts a reasonable expectation of privacy, such that a request by the police to obtain it constitutes a search under section 8 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. In 2017, the Calgary Police Services were investigating fraudulent online purchases from a liquor store. The police got the IP addresses used for the transactions and obtained a court order compelling the Internet service provider to disclose the name and residential address for the IP addresses. One was registered to Mr. Bykovets. The police used this information to obtain and execute search warrants at his home. Mr. Bykovets was arrested and convicted.

The Supreme Court allowed his appeal and ordered a new trial. The police’s request for Mr. Bykovets’ IP address was a search within the meaning of section 8 of the Charter. Writing for the majority, Justice Karakatsanis explained that an IP address is the crucial link between an Internet user and their online activity. She said “it is the key to unlocking a user’s Internet activity and, ultimately, their identity, such that it attracts a reasonable expectation of privacy”. Accordingly, a request by the state — in this case, the police — for an IP address is a search under section 8 of the Charter.

This case concerned 2 individuals convicted of sexual assault in separate and unrelated cases. The convictions were later overturned on the basis that the trial judge had made improper assumptions about human behaviour not supported by the evidence.

The Supreme Court confirmed the credibility and reliability findings by the trial judges and restored the men’s convictions. Writing for a majority, Justice Martin said that adopting a rule against ungrounded common-sense assumptions would represent a radical departure from how appellate courts have typically approached credibility and reliability assessments, especially in the context of sexual assault. She said the faulty use of common-sense assumptions in criminal trials should continue to be controlled by existing standards of review and rules of evidence. In some cases, a trial judge’s use of common sense will be vulnerable to appellate review because it discloses recognized errors of law. Otherwise, like with other factual findings, she said credibility and reliability assessments — and any reliance on the common-sense assumptions inherent within them — will be reviewable only for palpable and overriding error.

Consult the case information for R. v. Kruk

Consult the case information for R. v. Tsang

Cindy Dickson is a member of a First Nation community who wanted to stand for election as a Councillor. She argued that a residency requirement enacted by the First Nation discriminated against her as a non-resident of the settlement land, contrary to her right to equality guaranteed under section 15(1) of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. As a self-governing Indigenous community, the First Nation said that it did not fit the definition and scope of a “government” under section 32(1), and therefore, was not bound by the Charter. Alternatively, the First Nation argued that if it were bound by the Charter and the residency requirement did violate Ms. Dickson’s right to equality, it was protected by section 25 of the Charter. Section 25 states that the guarantee in the Charter of certain rights and freedoms must not be interpreted so as to abrogate or derogate from any Aboriginal, treaty or other rights or freedoms that belong to the Aboriginal peoples of Canada.

The Supreme Court upheld the residency requirement. Writing for the majority, Justices Kasirer and Jamal held that the Charter applied to the First Nation, but Ms. Dickson’s section 15 Charter challenge failed, because of the operation of section 25. The residency requirement is protected as an “other” right or freedom under section 25 because it preserves “Indigenous difference”. Ms. Dickson’s claim based on her section 15 right to equality abrogated or derogated from this “other” right under section 25. As such, her claim could not be given effect.

Consult the case information for Dickson v. Vuntut Gwitchin First Nation

This appeal looked at whether the breach of the Blood Tribe’s entitlement under an 1877 land treaty was actionable in Canadian courts before the coming into force of section 35(1) of the Constitution Act, 1982, which recognized and affirmed the existing Aboriginal and treaty rights of the Aboriginal peoples of Canada.

The Supreme Court ruled that the tribe’s treaty land entitlement claim is statute-barred, but that declaratory relief is warranted given the longevity and magnitude of the Crown’s dishonourable conduct. Writing for a unanimous Court, Justice O’Bonsawin explained that section 35(1) did not create a cause of action for breach of treaty rights. Treaty rights flow from the treaty, not the Constitution, and treaties are enforceable upon execution and give rise to actionable duties under the common law. Accordingly, the Blood Tribe’s claim was actionable prior to the coming into force of section 35(1). The Blood Tribe did not contest the trial judge’s finding that the claim was discoverable as early as 1971 or that the action was not commenced until 1980. As such, the claim is statute-barred by operation of the applicable 6-year limitation period.

However, Justice O’Bonsawin concluded that declaratory relief is warranted given the longevity and magnitude of the Crown’s dishonourable conduct towards the Blood Tribe.

“Declaratory relief will serve an important role in clarifying the Blood Tribe’s [treaty land entitlement provisions], identifying the Crown’s dishonourable conduct, assisting future reconciliation efforts, and helping to restore the honour of the Crown.”

Mr. Tayo Tompouba is a bilingual Francophone who was convicted of sexual assault following a trial conducted in English in the Supreme Court of British Columbia. During the judicial process, the judge did not ensure that Mr. Tompouba was advised of his right to be tried in French, contrary to the requirements of section 530(3) of the Criminal Code.

The Supreme Court ordered a new trial in French. Writing for the majority, Chief Justice Wagner stated that section 530(3) imposes a 2-pronged informational duty on the judge before whom an accused first appears: to ensure that the accused is duly informed of their fundamental right and of how it is to be exercised, and, where the circumstances so require, to take the necessary steps to inform the accused. As the Chief Justice explained, a breach of this duty taints the trial court’s judgment and gives rise to a presumption that the accused’s fundamental right to be tried in the official language of their choice was violated. The Crown can then rebut this presumption if it demonstrates that the error did not cause the accused any prejudice. In this case, the Chief Justice concluded, first, that Mr. Tompouba had proved that an error had been made and, second, that the Crown had failed to establish that Mr. Tompouba’s fundamental right had not in fact been violated despite the judge’s breach of his duty under section 530(3).

In this case, the Supreme Court dealt with how to protect the anonymity of a police informer while minimizing, as much as possible, any impairment of the open court principle.

The Supreme Court stated that court openness is a cardinal principle of the Canadian justice system, and any exception to this principle must be limited. In a unanimous judgment, the Court explained that where, as in this case, a police informer asserts their status in a proceeding that began publicly in which they face charges that do not cause them to lose their status, and the informer‑police relationship is central to the proceedings, the appropriate way to protect the informer’s anonymity will generally be to proceed totally in camera. Even in these most confidential of cases, it is still possible — and even essential — to protect the informer’s anonymity while favouring confidentiality orders that do not entirely or indefinitely keep the existence of a hearing or judgment from the public.

As the Court noted, when justice is rendered in secret, without leaving any trace, respect for the rule of law is jeopardized and public confidence in the administration of justice may be shaken. The open court principle allows a society to guard against such risks, which erode the very foundations of democracy. By ensuring the accountability of the judiciary, court openness supports an administration of justice that is impartial, fair and in accordance with the rule of law. It also helps the public gain a better understanding of the justice system and its participants, which can only enhance public confidence in their integrity. Court openness is therefore of paramount importance to our democracy.

“[T]he very concept of ‘secret trial’ does not exist in Canada […] . [T]he cardinal principle of court openness may be tempered where the circumstances of a case so require. […] But it is well established that ‘secret trials’, those that leave no trace, are not part of the range of possible measures.”

Consult the case information for Canadian Broadcasting Corp. v. Named Person

This appeal dealt with the question of whether the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms applies to Ontario public school boards.

2 teachers employed by an Ontario public school board recorded their private communications regarding workplace concerns on a shared personal, password-protected log stored in the cloud. With the teachers not present, the school principal accessed a Board laptop used by one of the teachers, read and documented their communications regarding workplace concerns. The school board then issued written reprimands against those teachers. The teachers’ union filed a grievance against the written reprimands issued to the teachers, claiming that the search violated the teachers’ right to privacy at work.

Writing for a majority of judges, Justice Rowe said Ontario public school board teachers are protected from unreasonable search and seizure in the workplace under section 8 of the Charter, as these boards are inherently governmental for the purposes of section 32 of the Charter. Section 32 identifies certain entities that are bound by the Charter, including federal and provincial legislatures and governments, as well as entities that are controlled by a government or that perform governmental functions.

This appeal is about whether the state is immune from liability for damages when it makes legislation that courts later find to be unconstitutional.

Joseph Power applied for a record suspension in 2013 but his application was denied. At the time of Mr. Power’s conviction in 1996, persons convicted of indictable offences could apply for a record suspension 5 years after their release. An indictable offence is a category of more serious criminal offences. Legislation enacted in 2010 and 2012 rendered Mr. Power permanently ineligible for a record suspension. This legislation was declared unconstitutional by courts in other proceedings. Mr. Power sought damages under s. 24(1) of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, arguing that his criminal record prevented him from working in the field in which he had trained.

The Supreme Court confirmed that the state may be required to pay damages for making unconstitutional legislation in limited circumstances. Writing for the majority, Chief Justice Wagner and Justice Karakatsanis held that the state is not entitled to an absolute immunity from liability for damages when it enacts unconstitutional legislation that infringes Charter rights. Rather, it may be liable for Charter damages if the legislation is clearly unconstitutional or was in bad faith or an abuse of power. An absolute immunity fails to properly reconcile the constitutional principles that protect legislative autonomy, such as parliamentary sovereignty and parliamentary privilege, and the principles that require the government be held accountable for infringing Charter rights, such as constitutionality and the rule of law. Each of these principles constitutes an essential part of Canada’s constitutional law and they must all be respected to achieve an appropriate separation of powers. By shielding the government from liability in even the most egregious circumstances, absolute immunity would subvert the principles that demand government accountability.

Consult the case information for Canada (Attorney General) v. Power

This judgment clarified the rights and obligations of the Crown and the Anishinaabe of Lake Huron and Lake Superior under 2 historic treaties and what the Crown must do to address its breaches of those treaties.

Under the treaties, the Anishinaabe agreed to cede their territories to the Crown in return for an annuity payment. The treaties also provided for the increase of the annuities over time under certain circumstances (the “Augmentation Clause”). The annuities were increased to $4 to each individual in 1875, but have not increased since then. The Anishinaabe filed claims against the Crown, alleging it had breached the Augmentation Clause and its fiduciary duty to act in the best interest of Indigenous Peoples.

The Supreme Court held that the Crown must negotiate or, failing agreement, determine the compensation it owes to the Anishinaabe for breaching its treaty promises. Writing for a unanimous Court, Justice Jamal said that the Crown has a duty to consider, from time to time, whether it can increase the annuities without incurring loss. If the Crown can increase the annuities beyond $4 to each individual, it must exercise its discretion and decide whether to do so and, if so, by how much. This discretion is not unfettered; it must be exercised liberally, justly, and in accordance with the honour of the Crown. The frequency with which the Crown must consider whether it can increase the annuities must also be consistent with the honour of the Crown. Given the longstanding and egregious nature of the Crown’s breach of the Augmentation Clause, the Crown must also exercise its discretion and increase the annuities with respect to the past.

Consult the case information for Ontario (Attorney General) v. Restoule

This appeal is about whether bankruptcy releases persons from having to comply with certain orders imposed on them by a regulatory agency for having broken the law.

Between 2007 and 2009, Thalbinder Singh Poonian and Shailu Poonian engaged in a scheme in which they manipulated the share price of a public oil and gas company and then sold the overpriced shares to investors. In 2014, the British Columbia Securities Commission found that the Poonians had violated the province’s Securities Act. They were ordered to pay $13.5 million in administrative penalties and $5.6 million in amounts they had obtained as a result of the scheme. In 2018, the Poonians went into bankruptcy and sought to be released from the orders to pay those amounts.

The Supreme Court concluded that bankruptcy does not release people from orders to pay amounts obtained by fraud, but could release them from administrative penalties. Writing for the majority, Justice Côté explained that orders to pay amounts that were obtained by fraud are directly linked to that fraud in a way that administrative penalties are not.

Consult the case information for Poonian v. British Columbia (Securities Commission)

A young person and her parents filed an application with a Quebec tribunal alleging an encroachment on her rights arising from her stay in a rehabilitation centre. The tribunal identified 4 violations and issued corrective orders. However, the director of youth protection (DYP) contested these orders, because they did not relate directly to the young person’s situation. The courts narrowed the scope of the tribunal’s orders and the Commission des droits de la personne et des droits de la jeunesse subsequently appealed to the Supreme Court of Canada.

The Supreme Court allowed the appeal in part. The purpose of the corrective measures must be to put an end to and remedy the effects of the encroachment upon rights on the child who is before the tribunal.

Writing for the Court, Chief Justice Wagner determined that the legislature intended to confer on the tribunal the corrective powers needed to ensure the fullest protection of the interests and rights of the child whose situation has been referred to it. This protection must apply to both the present and the future and must take account of the circumstances at the source of the encroachment upon rights as well as the impact of the encroachment on the child’s psychological and physical state. A preventive corrective measure can be ordered only if the child whose rights have been encroached upon is at risk of being subjected to the situation of encroachment again, if the corrective measure can effectively help to prevent the recurrence of the situation of encroachment, and if the measure is related to the protection of the interests and rights of the child whose situation has been referred to the tribunal.

All judgments

Related links

- Judgments – Learn more about the judgments of the Court.

- Cases in Brief – Read summaries of the Court’s decisions in plain language.

Outreach and education

Consistent with the principles of access to justice and open courts, the Court takes an active role in many different educational and outreach initiatives aimed at the public, students and educators, and legal professionals. These efforts are essential to strengthening trust in the judicial process.

Engaging the public

Like all courts in Canada, the Supreme Court is guided by the open court principle. Members of the public are invited to attend or watch hearings online, and may visit the Court to learn more about it and its work.

The Supreme Court offers public tours year-round, hosted by our knowledgeable, bilingual guides. Online tours are also available.

The Court also hosted 2 special open houses in 2024. In June, it was one of the stops of Doors Open Ottawa, a local event celebrating the city’s architectural history and heritage. The Court also welcomed visitors as part of Canada Day festivities in the national capital. Some 40,000 people from across Canada and around the world visited the Court in 2024.

Inspiring elementary and secondary students

The Supreme Court is dedicated to inspiring the next generation to become informed and engaged citizens by fostering an understanding of our judicial system. Each year, hundreds of school groups, ranging from elementary to secondary levels, visit the Court to participate in educational tours. Judges frequently take the opportunity to meet and interact with students at the Court and in the community.

To support teachers, the Court offers a downloadable educational kit that includes a poster, an activity book and resources to run a mock trial in the classroom.

A visit by the Teachers Institute on Canadian Parliamentary Democracy has also become an annual highlight for our judges. This unique program allows engaged law, civics and social studies teachers to experience Canadian public institutions up close, including the Supreme Court. Each year, participants get the chance to tour our building, sit in our courtroom and hear more about the work of a Supreme Court judge.

Empowering post-secondary students and young professionals

The Supreme Court is also proud to support post-secondary students and aspiring young professionals who will form the next generation of lawyers, judges, and civic leaders. Judges often speak with law students, academic groups, parliamentary interns and more. These interactions provide young Canadians with opportunities to learn more about the work of the Supreme Court and the judicial branch of government. Discussions often touch on topics like access to justice, judicial independence, and career paths in law and the judiciary.

Collaborating with legal professionals

Supreme Court judges are proud to collaborate with representatives of the legal profession to advance the justice system as a whole. Judges often speak with legal professionals as part of events hosted by national, provincial, and local bar associations and law societies.

In February, the Chief Justice addressed the Annual General Meeting of the Canadian Bar Association (CBA). His remarks focused on important issues such as judicial independence, access to justice, and mental health and wellness in the legal and judicial professions.

In June, Chief Justice Wagner and Justice Moreau took part in a panel discussion hosted by the Quebec branch of the CBA. They spoke about diversity and bilingualism on the bench, as well as the importance of strengthening judicial independence and public confidence in our institutions.

In October, judges hosted members of the Supreme Court Advocacy Institute, an organization that provides guidance to lawyers appearing before the Court. The Court’s engagement with lawyers and other professionals helps to advance the legal profession while promoting key principles like transparency and access to justice.

Representatives from the Court’s administration also collaborate with professionals from other courts to exchange ideas and share best practices in areas like communications, court modernization and more.

Supporting judicial education in Canada and around the world

The strength of our justice system depends on a highly skilled, dedicated, and professional judiciary. The Canadian Judicial Council, chaired by the Chief Justice, works to maintain and improve the quality of judicial services in Canada’s superior courts. The Chief Justice also serves as chair of the National Judicial Institute, an independent, judge-led organization that develops and delivers a range of educational programs for the judiciary.

The National Judicial Institute and the Canadian Institute for the Administration of Justice jointly deliver seminars twice a year for new federally appointed judges. At their spring seminar, the Chief Justice shared his thoughts on collegiality, mentorship, and well-being in the judicial profession.

In April, the Chief Justice met with executive members of the Canadian Association of Provincial Court Judges (CAPCJ). With the shared objectives of supporting access to justice and ensuring judicial independence, they discussed a broad range of topics, including judicial education, judicial vacancies and the use of technology by courts. CAPCJ is a federation of provincial and territorial judges’ associations with over 1,000 members across the country.

Promoting access to justice

Judges of the Supreme Court are strong proponents of the principle of access to justice. The challenges associated with access to justice have been well documented, and all representatives of the justice system have a role to play in solving them.

The leadership of the Action Committee on Modernizing Court Operations, co-chaired by the Chief Justice and the Minister of Justice of Canada, plays a crucial role in enhancing access to justice for all court users.

Justice Karakatsanis is also the chair of the National Action Committee on Access to Justice in Civil and Family Matters, which continues to explore new approaches to this important issue.

Members of the Court recognize the importance of initiatives like law clinics, legal aid programs, and pro bono or duty counsel services. Judges also acknowledge the work of grassroots organizations across Canada working to ensure the public understands their legal rights, has access to legal information, and knows where to find affordable legal representation.

In December, Chief Justice Wagner had the opportunity to visit the Kensington-Bellwoods Legal Aid Clinic in Toronto to meet volunteers from Pro Bono Students Canada and see them in action. With the support of students from Toronto Metropolitan University and the University of Toronto, the clinic provides free legal services to low-income residents of the community. It is just one of many such legal clinics in communities all across Canada.

Such initiatives contribute to making justice more equitable and accessible to all.

“We have seen the impact of disparities in access to justice. As a society, we cannot afford to continue to make that mistake. There is a professional and ethical responsibility to do pro bono, but more than that, it is tied to the type of society we want to live in.”

— The Right Honourable Richard Wagner, P.C.

Chief Justice of Canada

International engagement

The Supreme Court of Canada is recognized as a leader in the international judicial community. Court members and staff often liaise with their counterparts from around the world to promote the importance of key principles like openness, access to justice and judicial independence.

Judicial exchanges

Judicial exchanges with other courts around the world provide unique opportunities for judges to share best practices and discuss topics of mutual interest.

In March, Chief Justice Wagner and Justice Moreau took part in a judicial exchange hosted by Chief Justice Raymond Zondo and his colleagues from the Constitutional Court of South Africa. The 2 delegations discussed judicial independence, the judicial nomination process and judicial conduct. This was the first judicial exchange between the 2 courts.

In April, the Supreme Court of Canada was honoured to welcome representatives from the Constitutional Court of Slovenia as part of the first-ever judicial exchange between our 2 courts. The delegation from the Supreme Court of Canada consisted of Chief Justice Wagner, and Justices Côté, Martin and Jamal. The delegation from the Constitutional Court of Slovenia included President Dr. Matej Accetto, Vice President Dr. Rok Čeferin, and Judge Dr. Katja Šugman Stubbs. The judges discussed their respective countries’ jurisprudence as well as legal issues such as freedom of expression, equality and women’s reproductive rights, and artificial intelligence.

The Chief Justice was honoured to participate in the J20 Summit held in Rio de Janeiro in May. The J20 Summit assembled the heads of supreme and constitutional courts of the G20 members. This was the first time a Chief Justice of Canada attended the J20.

International judicial organizations

The Supreme Court of Canada is a proud member of international judicial organizations such as the Association of Francophone Constitutional Courts (ACCF), the Association des Hautes Juridictions de Cassation des pays ayant en partage l’usage du français (AHJUCAF), the Commonwealth Magistrates’ and Judges’ Association, the International Association of Supreme Administrative Jurisdictions and the World Conference on Constitutional Justice.

The ACCF brings together 50 constitutional courts and equivalent institutions from Africa, Europe, America and Asia, and seeks to strengthen the rule of law through judicial cooperation and conversations between francophone courts. Chief Justice Wagner was honoured to chair the ACCF’s executive committee meeting in Albania in February, and moderated a panel on challenges faced by democracies in protecting freedom of expression at the ACCF’s annual meeting in Paris in June.

AHJUCAF is an international association whose members include apex courts from French-speaking countries. Chief Justice Wagner and Justices Côté and Kasirer were pleased to welcome a high-level delegation from AHJUCAF to Ottawa in October. Delegates had the opportunity to discuss the role of francophone courts, as well as principles like the rule of law, judicial independence and access to justice.

The Court’s engagement in such organizations provides opportunities to learn more about how courts around the world are tackling common challenges and discuss practical solutions that prioritize access to justice.

In January, Chief Justice Wagner spoke at the 6th judicial seminar of the International Criminal Court on securing meaningful justice for victims, in The Hague, Netherlands. The Chief Justice also discussed the role of the rule of law in strengthening peace and justice with representatives from the international community and different courts, including the International Criminal Court, the International Court of Justice, the Permanent Court of Arbitration, the Supreme Court of the Netherlands and the Hague Conference on Private International Law.

In October, Chief Justice Wagner and Justice Karakatsanis shared their perspectives on strengthening democracy through access to justice with participants of the 2024 Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Global Roundtable on Equal Access to Justice. Delegates included representatives from many different countries.

Welcoming visiting delegations

Meetings with foreign visitors and delegations provide important opportunities to discuss a broad range of matters such as court modernization, judicial cooperation and the rule of law. Discussions often touch on matters of common interest — like the rule of law, use of technology in the courts, outreach and communicating with the public, the impact of technology and the appointment process.

Throughout the year, judges and court administration officials also welcomed representatives and delegations from many different countries, including Czechia, Germany, Indonesia, Italy, Japan, Lithuania, Nigeria, Norway, Pakistan, Vietnam, among others.

150 years of the Supreme Court of Canada

In 2025, the Supreme Court of Canada is recognizing its 150th anniversary under the theme “150 years of upholding the Rule of Law, building public trust, and serving our community.”

Since April 8, 1875, the Supreme Court has served Canadians by deciding legal issues of public importance. As guardian of our Constitution and protector of our rights and freedoms, its decisions have provided the legal foundation for a strong and democratic country.

Today, the Court stands as a shining beacon for democracy, recognized around the world as a champion for the fundamental principles of openness, transparency and judicial independence and its service to Canadians.

Anniversary initiatives

The Supreme Court is marking this important milestone through a series of events and initiatives intended to enhance awareness of the Court’s work and strengthen public confidence in our justice system. The legal community, the public and the media are all invited to participate.

Visits to 5 Canadian cities

Building on the success of the Court’s visits to Winnipeg in 2019 and Quebec City in 2022, judges are visiting 5 communities across Canada throughout 2025. The visits provide opportunities for members of the public, high school and university students, journalists, and the legal and judicial communities to engage with members of the Court.

- Victoria, British Columbia

February 3–4, 2025 - Moncton, New Brunswick

March 10–11, 2025 - Yellowknife, Northwest Territories

September 14–15, 2025 - Sherbrooke, Quebec

October 21–23, 2025 - Thunder Bay, Ontario

November 17–18, 2025

Essay and art competitions

An essay competition for law students focuses on the Court’s landmark decisions. The Court has also launched an art contest for young Canadians aged 5 to 17 years old.

Legal symposium (April 10–11, 2025)

This bilingual symposium for judges of the Supreme Court, other Canadian and international courts, and the legal community examines the Court’s role in the justice system and how it can continue to meet the changing needs of society.

Law clerk reunion (June 13–15, 2025)

This reunion brings together current and former Supreme Court judicial law clerks in Ottawa.

Opening of the judicial year (October 6, 2025)

This event will provide an opportunity for the legal community to come together and reflect on current issues facing the justice system. Reviving an old tradition, this will be the first ceremonial opening at the Supreme Court in nearly 4 decades.

Special historical exhibit in the Supreme Court of Canada’s grand entrance hall

A special exhibit will explore the Court’s early history through original documents like the Proclamation of the Constitution Act, 1982, the Supreme and Exchequer Court Act and more. Presented in collaboration with Library and Archives Canada and the Senate of Canada.

Outdoor exhibit in downtown Ottawa

A free, outdoor exhibit in downtown Ottawa will retrace the Court’s history and role in our democracy. Presented in collaboration with the Department of Canadian Heritage.

Anniversary logo

The 150th anniversary logo reflects both the history and future of the Supreme Court.

The laurels signify growth, with new leaves symbolizing the Court’s continuous development and expansion into future generations. The 9 laurel leaves represent its 9 judges.

The shapes of the numbers reflect both the Court’s crest and its heraldic traditions.

Interwoven numbers symbolize the bijuralism and bilingualism of Canada’s justice system.

Related link

150 years of the Supreme Court of Canada – Read about the initiatives commemorating the Court’s 150th anniversary.

Connect with the Court

The Supreme Court of Canada is an international leader when it comes to promoting the open court principle. Its dedicated staff serve Canadians by promoting awareness of the Court and upholding the values of fairness, access and openness, which are at the core of our justice system.

Judges are supported by a team of talented legal professionals in a variety of roles — from lawyers, to jurilinguists, to law clerks and administrative personnel. This devoted team is there to ensure the Court operates safely, transparently and efficiently.

Here are some of the other ways Court staff are here for you:

Court registry: The Court registry assists individuals submitting filings or appearing before the Court. Each year, staff respond to thousands of inquiries from counsel, self-represented litigants and the public.

Access to case information: Extensive case information is available on the Supreme Court of Canada website. You can search the Supreme Court docket to view the status of a case and find links to relevant documents, including factums, counsel sheets, and judgments. Staff in our Records Centre are available to assist with more advanced inquiries.

Library: The Supreme Court’s library houses one of Canada’s most extensive legal collections for use by the Court’s judges, lawyers and law clerks. Other users of the library include lower court judges, members of the bar, law professors and individuals with special authorization.

Services for media: The Court supports journalists in their work of reporting on legal matters by informing them of hearings and judgments, fielding their inquiries, and holding briefings on all judgments. In addition, the Chief Justice holds an annual news conference to update the media and public on the work of the Court. Read additional information on resources for media.

Cases in Brief: In order to help more people understand the legal issues and outcome of the Court’s decisions, plain-language summaries, called Cases in Brief, are published for every judgment.

Year in Review: The Court summarizes its activities and initiatives each year in this report. Consult past editions of the Year in Review.

Social media: The Court also provides timely updates on its activities on its social media channels, which include LinkedIn, Instagram, YouTube and Facebook.

Website: The Supreme Court recently launched a refreshed website, making it more accessible and easier to navigate. The website will continue to provide timely, accurate and relevant information, with an improved design to enhance the user experience.

Visit the Supreme Court of Canada

The Supreme Court of Canada building is open to visitors on weekdays from 9 am to 5 pm.

Take a guided tour: Tours are offered year-round in both English and French. During the summer months, reservations are not required but recommended for groups of 10 or more. Tours are available at all other times of the year by reservation only. For more information, contact us at tour-visite@scc-csc.ca.

Participate in a remote tour: You are invited to join us for a virtual tour, which includes a presentation on the role and function of the Court from one of our knowledgeable, bilingual guides. For reservations, contact us at

tour-visite@scc-csc.ca.

Attend a hearing: Most hearings are open to the public, except when a sealing order requires that a proceeding be held in a closed session (in camera). Hearings are held from fall to spring. Consult the hearing schedule and reserve your seat by contacting bookingregistry-reservationgreffe@scc-csc.ca.

Watch online: You may also view hearings both live and on-demand on the Court’s website. Whether you choose to follow proceedings in person, online, or on television, simultaneous interpretation is available in both English and French.

Statistics

Statistical summary

In each Year in Review, the Supreme Court of Canada publishes a statistical summary of cases filed, heard, and decided over the preceding year. This report serves as a valuable reference tool for media, researchers, and the public, offering a quantitative view of the Court’s caseload.

Responding to recent feedback, and in keeping with principles of accessibility and transparency, this year’s report presents the data in a new, more concise format, making it easier for users to find and interpret Court statistics.

Caseload

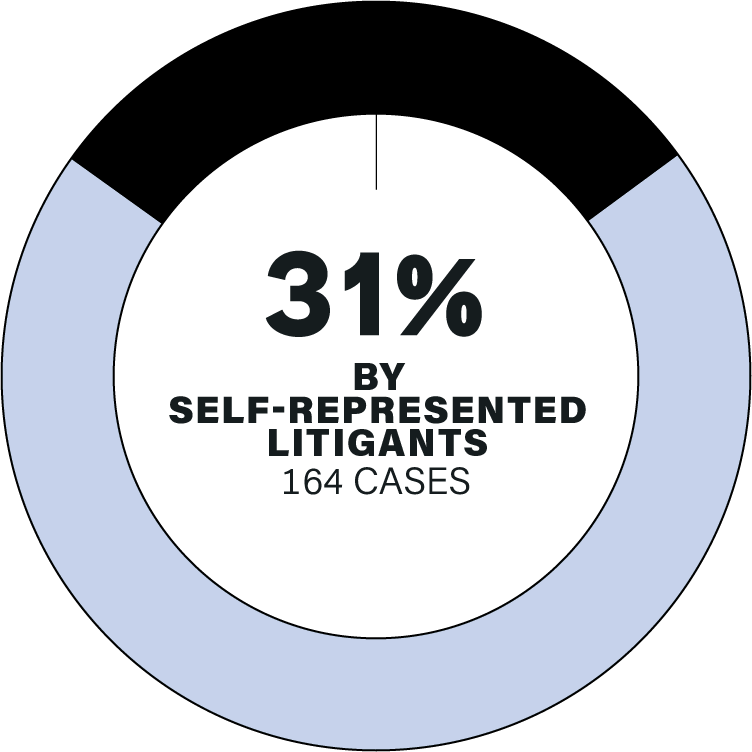

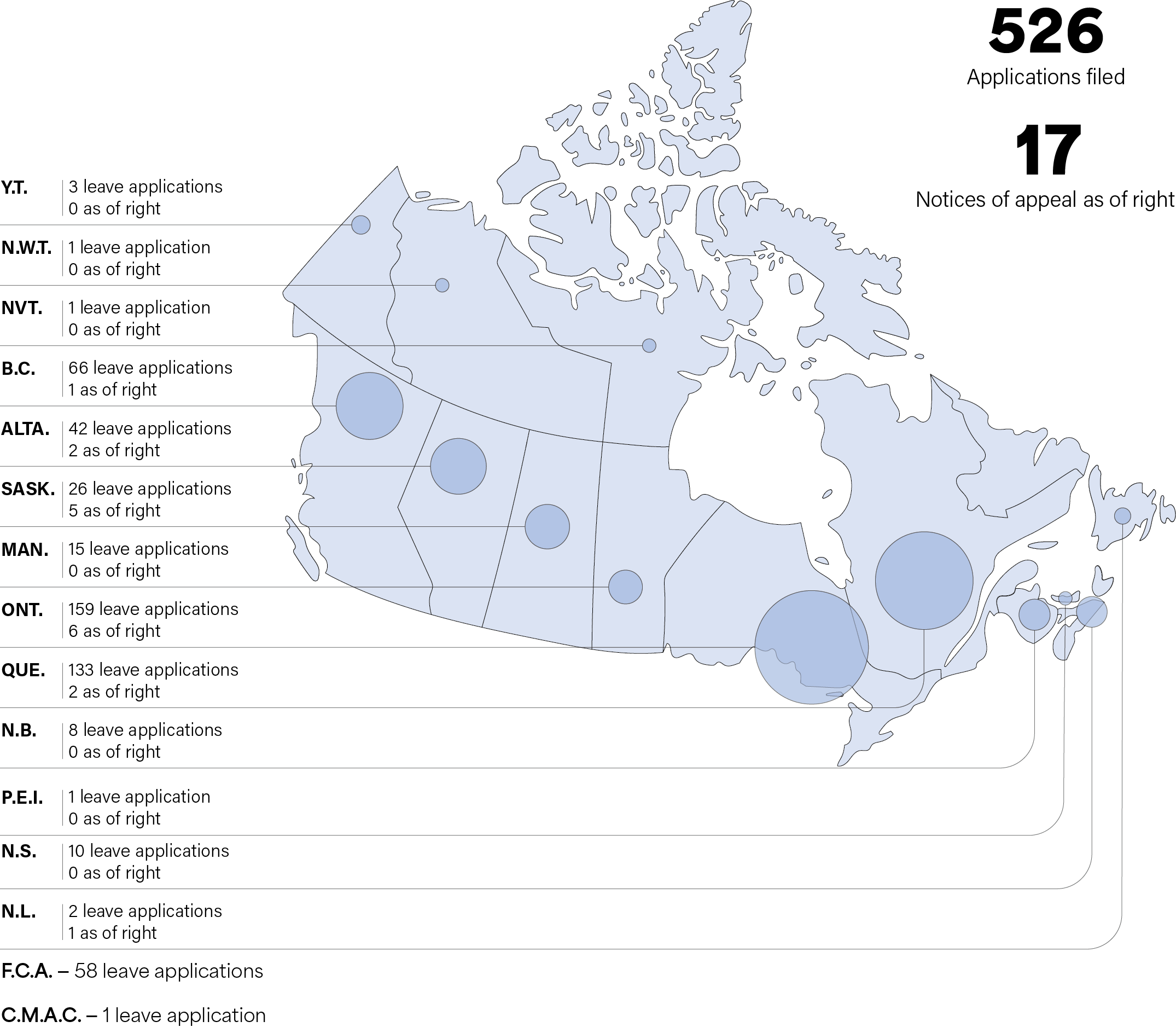

In 2024, the Court received 526 applications for leave, or permission to appeal, and 17 notices of appeal as of right. Most of the applications for leave to appeal were filed by lawyers on behalf of their clients, but 31% were filed by self-represented litigants, a slightly higher percentage than in 2023.

There are 3 numbers that are important when looking at applications for leave to appeal. First, there is the number of leave applications filed, 526 in 2024, as noted above. Second, there is the number of leave applications that are submitted to the judges as being complete for decision. In 2024, that number was 534. These 2 numbers are different because leave applications filed in 1 year may not be completed by the parties or ready for decision by the judges until the next year. Third, there is the number of leave applications that are granted. The Court grants leave to appeal when the judges are of the opinion that the proposed appeal meets the test of public importance as set out in section 40 of the Supreme Court Act. In 2024, the Court granted 35 applications for leave to appeal. 3 of the judgments granting leave related to applications that were given to the judges for decision late in 2023. The Court does not give reasons for its decisions on leave applications.

The Court heard 39 appeals in 2024; 19 in the first half of the year and 20 between October and December. The low number of appeals heard between January and June reflects the lower number of filings due to the pandemic slowdown in the courts. The fall 2024 session was full, and the Court expects a normal caseload going forward.

In 2024, the Court rendered 50 judgments, 14 more than in 2023. 38% of the appeal judgments were unanimous.

The average time between the hearing of an appeal and the judgment was 6.4 months.

A word about the data

The data on the following pages reflect the calendar year (January 1 to December 31). However, a case’s time on the Supreme Court docket can extend from one calendar year into another. This means that:

- Leave applications filed in one year may not necessarily be submitted or decided in the same year;

- Leave applications granted in one year may not necessarily be heard in the same year; and

- Judgments may not necessarily be rendered in the same year as the case hearing.

For example, most appeals heard in the fall of one year are decided in the winter or spring of the following year.

In addition, appeals with issues in common may be decided in the same judgment, even if the Court hears them separately.

For this reason, some differences are to be expected in the yearly statistics from one category to the next.

10-year trends

It is worth noting that due to widespread court closures across Canada from 2020 to 2022 due to the COVID-19 pandemic, some anomalies and irregularities are to be expected in the 10-year data.

Common terms used in the statistical summary

The documents filed to ask permission are known as the applications for leave to appeal (or leave applications).

When the Court gives permission for an appeal to be heard, the leave application is said to be granted. Conversely, when the Court does not give permission for an appeal to go forward, it is said to be dismissed.

The final decision ending an appeal is often referred to as the Court’s judgment. When the Court overturns the lower-court decision, the appeal is said to be allowed. When the Court agrees with the lower-court decision, it is said to be dismissed.

The decision of the Court is sometimes rendered at the conclusion of the hearing. This is known as an oral decision, or a judgment from the bench. More often, judgment is reserved to enable the judges to write considered reasons, which explain how they arrived at their decision.

Decisions of the Court need not be unanimous; a majority may decide, with dissenting reasons given by the minority. Each judge may write reasons in any case if he or she chooses to do so. When a decision is not unanimous, it is known as a split decision.

Cases filed

| 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complete applications for leave to appeal filed | 542 | 577 | 526 | 531 | 534 | 481 | 492 | 486 | 523 | 526 |

| Notices of appeal as of right | 21 | 15 | 17 | 26 | 25 | 25 | 21 | 23 | 10 | 17 |

| Leave applications submitted to the Court | 483 | 598 | 492 | 484 | 552 | 483 | 430 | 451 | 563 | 534 |

| Granted (pending) | 43 | 50 | 50 | 42 | 36 | 34 | 34 | 31 | 34 | 34 (19) | Percentage granted | 9 | 8 | 10 | 9 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 6 |

Applications filed by self-represented litigants

Applications by category

Cases filed — by origin

Appeals heard

| 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number | 63 | 63 | 66 | 66 | 69 | 41 | 58 | 52 | 49 | 39 |

| As of right | 15 | 15 | 17 | 21 | 24 | 19 | 26 | 19 | 15 | 11 |

| By leave | 48 | 48 | 49 | 45 | 45 | 22 | 32 | 33 | 34 | 28 |

| Hearing days | 50 | 53 | 60 | 59 | 58 | 35 | 58 | 48 | 46 | 40 |

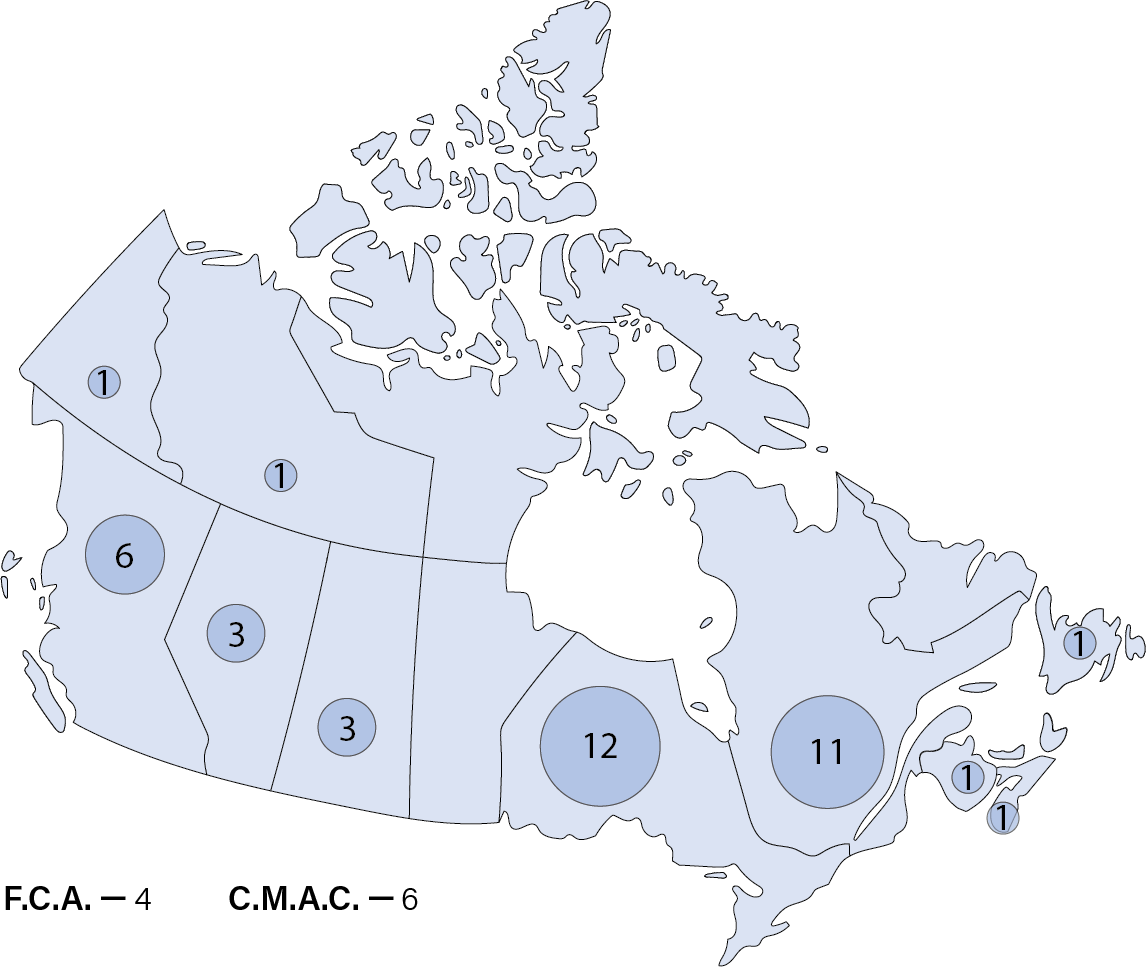

By origin

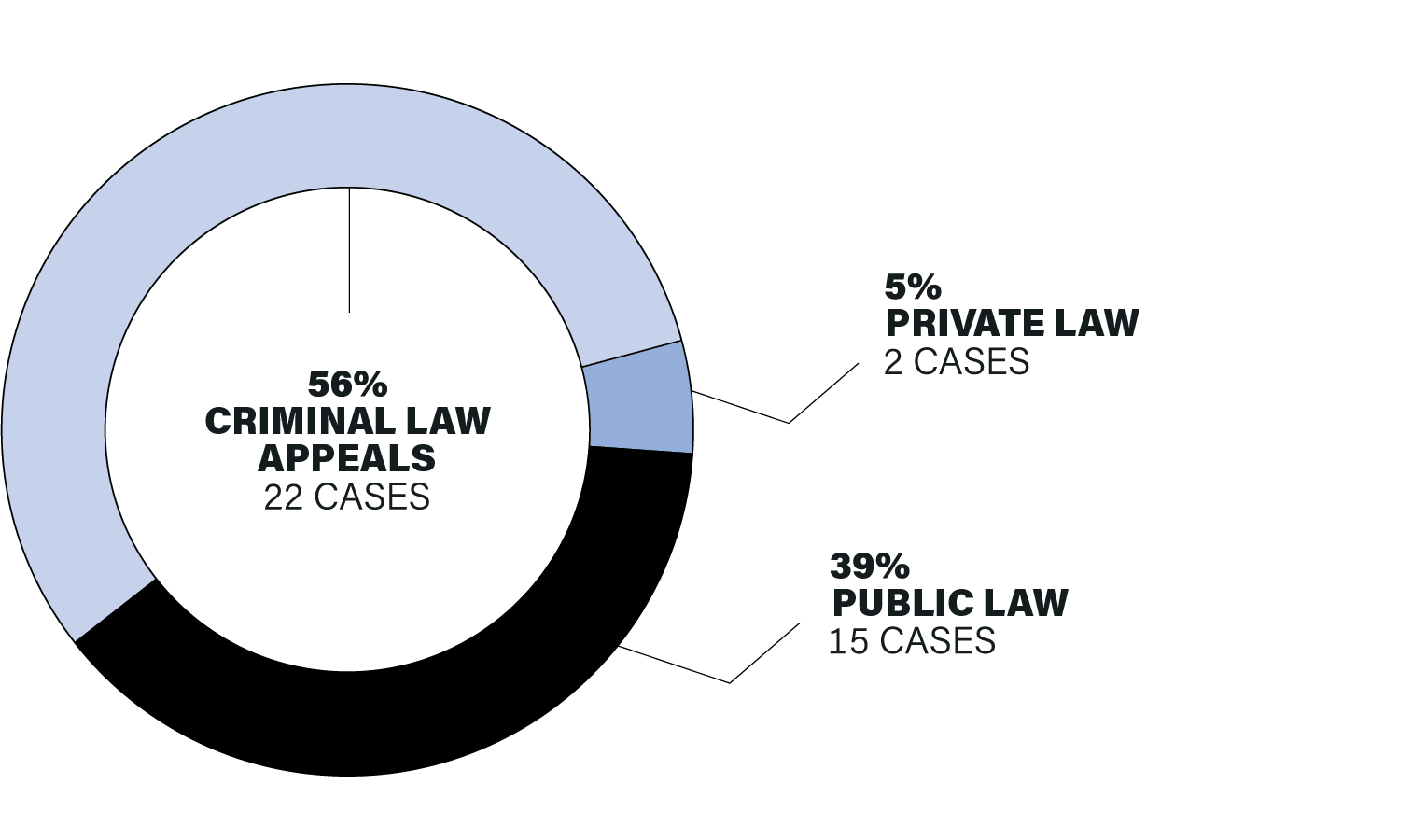

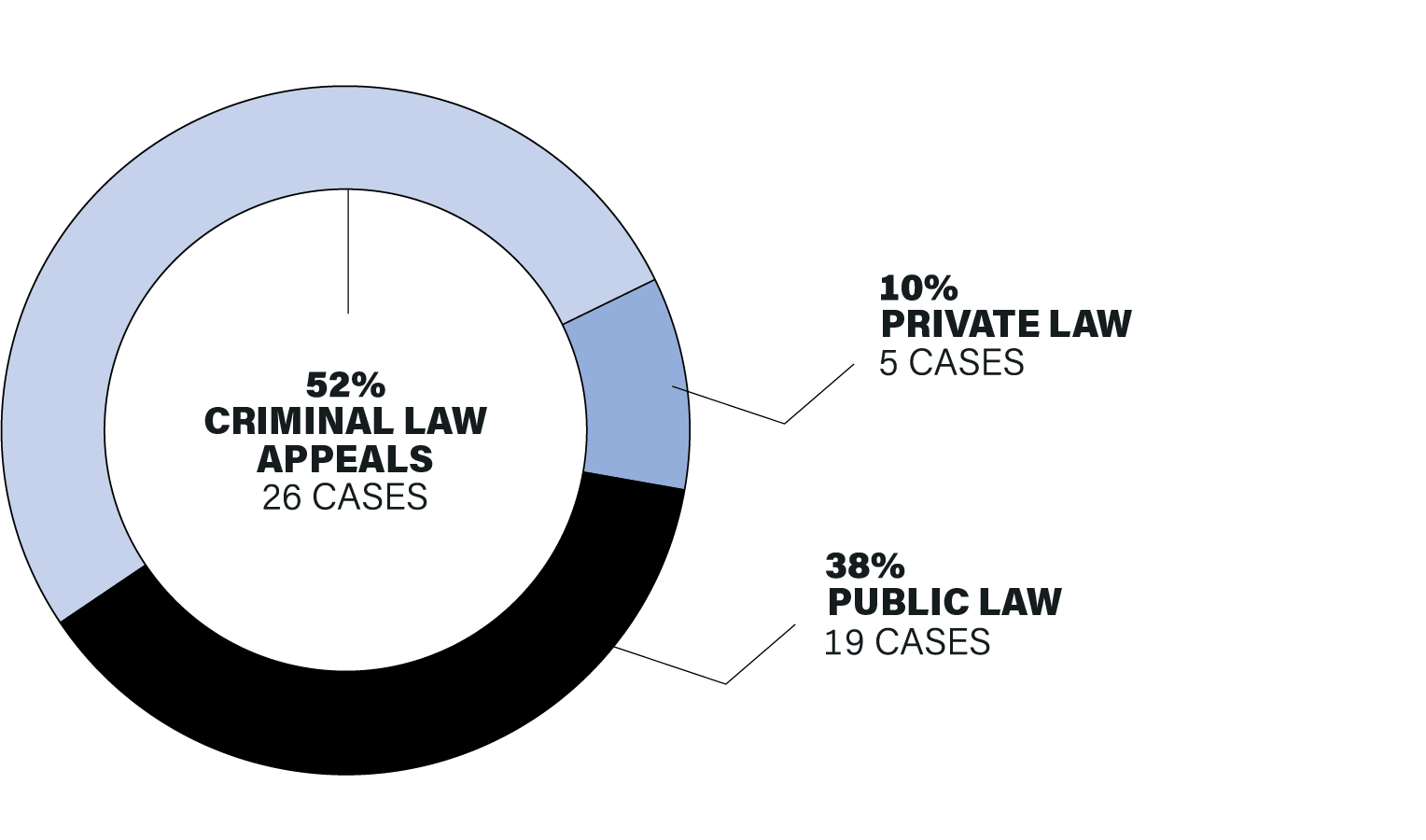

By category

Appeals decided

| 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number | 74 | 57 | 67 | 64 | 72 | 45 | 59 | 53 | 36 | 50 |

| Delivered from the bench | 16 | 13 | 19 | 20 | 25 | 17 | 22 | 17 | 10 | 8 |

| Delivered after being reserved | 58 | 44 | 48 | 44 | 47 | 28 | 37 | 36 | 26 | 42 |

| Appeals allowed | 35 | 29 | 28 | 33 | 39 | 24 | 22 | 20 | 18 | 20 |

| Appeals dismissed | 39 | 28 | 39 | 31 | 33 | 21 | 37 | 33 | 18 | 30 |

| Unanimous | 52 | 35 | 36 | 31 | 30 | 22 | 27 | 29 | 21 | 19 |

| Split | 22 | 22 | 31 | 33 | 42 | 23 | 32 | 24 | 15 | 31 |

| Percentage of unanimous judgments | 70 | 61 | 54 | 48 | 42 | 49 | 46 | 55 | 58 | 38 |

| Appeals standing for judgment at the end of each year | 18 | 24 | 25 | 25 | 26 | 20 | 21 | 16 | 30 | 19 |

| 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Between filing of application for leave and decision on application for leave | 4.2 | 4.1 | 4.0 | 5.8 | 4.3 | 3.6 | 3.0 | 3.9 | 4.6 | 4.3 |

| Between date leave granted (or date notice of appeal as of right filed) and hearing | 7.3 | 7.5 | 7.4 | 6.7 | 6.3 | 8.6 | 8.2 | 8.6 | 9.9 | 9.4 |

| Between hearing and judgment | 5.8 | 4.8 | 4.6 | 4.8 | 5.3 | 5.4 | 4.2 | 4.6 | 5.5 | 6.4 |

By origin

By category

Photo credits

All photos (except those listed below): Supreme Court of Canada Collection

Portrait of Justice Karakatsanis: Jessica Deeks Photography

Portrait of Justice Côté : Philippe Landreville, photographe

Portrait of Justice Rowe: Andrew Balfour Photography

Photo of Chief Justice Wagner with volunteers from Pro Bono Students Canada: Sage Whitworth, The Neighbourhood Group Community Service

Photo of Chief Justice Wagner and Justice Moreau at a Canadian Bar Association panel discussion: Canadian Bar Association (Quebec)

Photo of the audience at a Juripop event: Catherine Deslauriers

Footnote

- Footnote 1

-

Neutral citation to follow